[Editor’s Note: Welcome to Diary of a Web Series, the column that offers you an entertaining look into the machinations of a zero-budget web series made possible by an idea, fortitude, and democratized tools of production. For all the background on why we started publishing Diary of a Web Series — and why we think it’s great — check out the first installment right here. You can watch the web series the diary is about, too. It’s called STRAY and it’s good. Click here to watch it. And you can catch all the installments of Diary of a Web Series right here.]

When I set out to make my first web series in 2016, I felt like I was part of an emerging underground. Insecure and High Maintenance, cable TV iterations of web series, had just premiered on HBO. An air of possibility abounded among digital creators––the collective feeling that the web series had arrived in earnest. Workaholics might have written the playbook for the web series-to-network success story, but Broad City turned it into a New York Times bestseller. Unfortunately, I had arrived just in time for what iconic music critic Lester Bangs called “the death rattle, the last gasp.”

The web series was dead.

Subscribe for daily Tubefilter Top Stories

New York Indie Scene

I stumbled onto the scene full of zest and hope, immersing myself in the world of independent digital creators and filmmakers in New York. I participated in #WebSeriesChat on Twitter, where I met a filmmaker friend and future collaborator, Bri Castellini, and where I discovered Stareable, a repository of web series and a resource for independent creators. Stareable introduced me to meetups for creators–and, later, to film festivals.

Through Stareable, I met a collection of digital creators with a broad range of styles and perspectives, including:

- Bri Castellini (Sam and Pat Are Depressed)

- Jonathan Kaplan and Marianne Bayard (Killing It!)

- Darian Dauchan (Brobot Johnson)

- Taylor Coriell (You’re the Pest)

- James Boo (1 Minute Meal)

- Arthur Vincie (Three Trembling Cities)

- Brittany Tomkin and Jorja Hudson (Myrtle and Willoughby)

- Carl Foreman, Jr. (Frank and Lamar)

- Adrian Parks (Headshots)

So Many Web Series!

I consumed heaps of digital content, stuff that you just couldn’t find on linear TV or big streaming services. These were shows that either took chances with format and technique, or offered a point of view we normally don’t see. It was a feast of uproarious and touching web series, including, in addition to those mentioned above:

- The Gay and Wondrous Life of Caleb Gallo (Brian Jordan Alvarez)

- Only in HelLA (Rory Uphold)

- The Feels (Tim Manley, Naje Lataillade)

- Almost Asian (Katie Malia)

- Best Thing You’ll Ever Do (Monica West)

- Her Story (Jen Richards, Laura Zak)

- 20 Seconds To Live (Ben Rock, Bob Derosa)

- Brown Girls (Fatimah Asghar)

- Multiplex 10 (Gordon McAlpin)

- The Play (Bryony Cole)

- Convos with My 2-Year-Old (Matthew Clarke)

- Stupid Idiots (Stephanie Koenig)

- Arun Considers (Arun Narayanan)

This isn’t anywhere in the vicinity of comprehensive, of course, but it’s meant to illustrate the astonishing variety that can be found online. That variety is thanks to the proverbial democratization of media, but that accessibility comes with a cost: a crowded field with a lot of noise–and, as a result, a stigma. The new media equivalent to “read my screenplay” had emerged: “Check out my web series!”

From Peak To Petering Out

The stigma was in place long before I showed up, of course, but there was a brief period of time, roughly between 2014 and 2017, during which it seemed like the stigma might be dispelled. Web series were getting picked up left and right. (OK, that’s not true, but it felt that way).

The media took notice. In 2016, Vice published the piece How Web Series Have Widened TV’s Talent Pool, and not long after, The Verge published In 2017, the web series may be the new TV pilot. Brown Girls was poised to become the next web series-to-network sensation when it was picked up by HBO in 2017, but it never premiered. I don’t know if the show is still in development, but that delay marked the unofficial end of the golden era of web series.

Today, you don’t see much media coverage of web series, unless it’s celebrity-driven (Hot Ones, for example), supplementary content for a major media brand, or an Indian web series. You rarely see reviews about little-known indie web series, or web series roundups from festival winners. Indie festivals, like Brooklyn Web Fest, have come and gone.

Online opportunities for digital creators have dwindled. Digital network Super Deluxe, once a web comedy mainstay, faltered, came back to life, then died for good in late 2018, after AT&T bought Time Warner and proceeded to ruthlessly trim its streaming offerings. Online comedy giants like Funny or Die were forced into sweeping layoffs. Just a few weeks ago, CollegeHumor let most of its staff go, and only remains in business now because its longtime chief creative officer, Sam Reich, worked out a deal to take primary ownership.

It’s not that web series no longer exist, of course; it’s that its viability as a medium for indie creators is uncertain. Late last year, Adam Conover, star of CollegeHumor’s Adam Ruins Everything, lamented the demise of what he called “the emerging middle class of content creation.”

He’s right. Where has that internet middle class gone?

Where Do We Go From Here?

I’ve watched New York-based web series creators move out west to pursue more “legitimate” avenues. Some have abandoned web series entirely. Some continue to slog through the crowdfunding model. Several months ago, I reached out to the creator of one of my all-time favorite web series to ask if she was planning on making more episodes, as it had been a couple of years since she’d posted a new one. She told me that most of the online video places were gone, and the landscape had changed too much. It’s hard to argue against that.

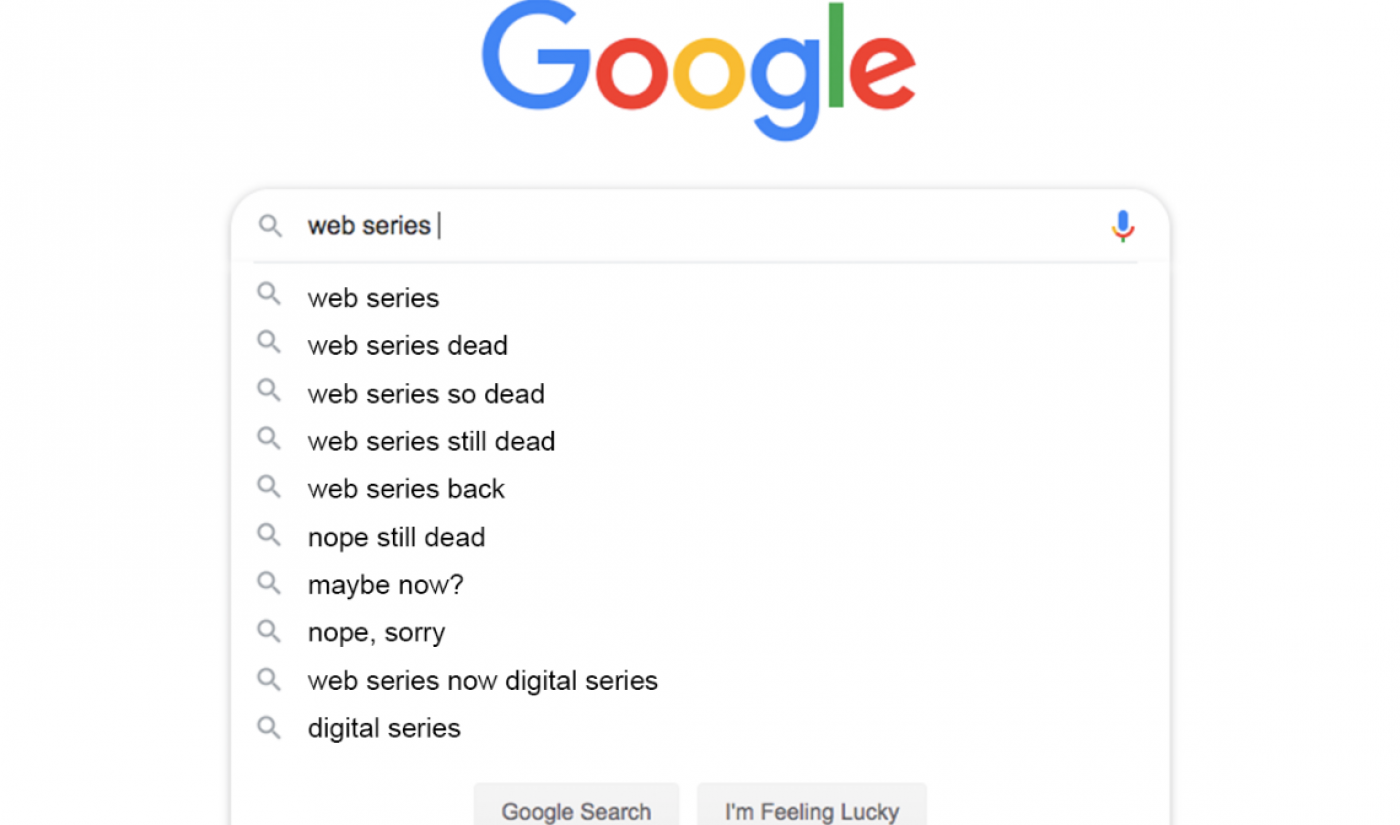

I’ve even noticed some creators keeping the term “web series” at arm’s length. They’ve rebranded their web series as “short series,” “original series,” or “digital series,” as if the term “web series” has become radioactive. Digital cooties.

Part of that, I suspect, is the low barrier to entry for making a web series. Democratization is good, but it does present challenges, not least of which is separating yourself from the pack. Validation is hard-won, unless you have staggering numbers that can’t be ignored, but that’s becoming increasingly elusive for web series creators.

Take YouTube as an example. Its algorithm used to favor shortform content, whereas now, in a bid to sell more ad inventory, YouTube prioritizes longer content in the 10- to 12-minute range. This, coupled with rewarding channels that post consistently, favors other formats, like the more cheaply made vlog.

All of which leads me to this question:

What’s The Point of Making A Web Series?

If you’re trying to build a big enough follower/subscriber base to sustain your creative pursuits, a web series is not a cost-effective path (Eastsiders and its recent pickup by Netflix notwithstanding). If you’re trying to secure a network deal, the web series isn’t–and probably never was–a good bet.

So, if it can’t sustain itself, and if it likely won’t lead to something bigger, why make one?

I can only answer for me: I keep making them because I have stories I want to tell and share that don’t work in other formats. I’m trying to carve a niche for them. I’m searching for their audiences. Not because I’m hoping to gain a million subscribers, or attract an agent or a development exec (although any of those things would be nice).

I owe it to all the people who worked on these web series. Those who supported, financially or otherwise. Those who watched. And the indeterminate contingent out there with whom these shows might resonate. And that’s what it’s really about: community. Telling a story in a certain way is what drew me to web series, but that sense of camaraderie and belonging is what hooked me on them.

The question that remains, however, is, how many more times can I eke my way through funding and making a web series? Umm, they’re not web series, thank you very much. They’re digital series!

Pablo Andreu is not a creator or a scriptwriter. He’s certainly not a filmmaker. He’s just a guy who decided to make a web series called STRAY, which is part of his comedy channel, Pygmy TV. He hopes it’s funny. By some inscrutable alchemy, his scribblings have wormed their way into The New York Times, McSweeney’s, and Slackjaw.

Pablo Andreu is not a creator or a scriptwriter. He’s certainly not a filmmaker. He’s just a guy who decided to make a web series called STRAY, which is part of his comedy channel, Pygmy TV. He hopes it’s funny. By some inscrutable alchemy, his scribblings have wormed their way into The New York Times, McSweeney’s, and Slackjaw.